A PDF of this 60 page adventure is available on DriveThruRPG. An introductory delve into a densely interactive classic dungeon crawl designed with contemporary sensibilities.

RPGS Aren't Played As They Were In The 1970’s And Even Classic RPG Design Must Grapple With It!

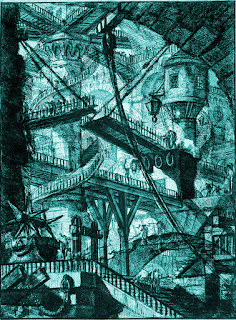

While the essay notes that I use the term Classic to perhaps describe something different then it’s version of Classic play, I’m not sure I fully agree. Yes, All Dead Generations frequently suggests rule variation from the primary sources of what Retired Adventurer identifies as the Classic style (AD&D and 1981’s Moldvay/Cook Basic and Expert books) and certainly my preferred aesthetics of phantasmagoric Western or opium fever Dunsanyian fantasy are somewhat far removed from the Gygaxian vernacular fantasy of gray stone corridors full of orcs that make up most classic adventures, but as far as ethics of play and play-style goals I place both All Dead Generations and my adventure design firmly in the Classic tradition. Why the distinction then? There are certainly still plenty of designers working with the Gygax aesthetic, and perfecting adventure design that reflects back to Keep on the Borderlands or even Castle Greyhawk. I’m not, and moreover the entire purpose of Jewelbox Design is somewhat antithetical to the maximal dungeons traditional for Classic play.

I’d argue that All Dead Generations and my current dungeon design seek to offer the same sort of “progressive development of challenges” and fairness that are the core of Classic design, but make them functional for contemporary play. By contemporary play I don’t mean 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons or its design principles, I mean the actual physical conditions that most RPGs seem to be played in in 2021. Two or three hour sessions, played at most once a week seems the modern standard, especially for online play. This is very different then how Gygax and other early designers appear to have run their tables and visualized play. While it’s a bit hard to pin down the exact length of Gygax’s sessions for Castle Greyhawk, Gygax notes in the April 1976 issue of the Strategic Review that:

“It is reasonable to calculate that if a fair player takes part in 50 to 75 games in the course of a year he should acquire sufficient experience points to make him about 9th to 11th level, assuming that he manages to survive all that play. The acquisition of successively higher levels will be proportionate to enhanced power and the number of experience points necessary to attain them, so another year of play will by no means mean a doubling of levels but rather the addition of perhaps two or three levels. Using this gauge, it should take four or five years tosee 20th level. As BLACKMOOR is the only campaign with a life of five years, and GREYHAWK with a life of four is the second longest running campaign, the most able adventurers should not yet have attained 20th level except in the two named campaigns. To my certain knowledge no player in either BLACKMOOR or GREYHAWK has risen above 14th level.”

The important context here is that while the number of sessions played is somewhere around one or two a week (though Gygax apparently ran Greyhawk more often with different groups), the length of the campaign is assumed to be many years. The length of session also seems to have generally been far longer. The original announcement for Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign read “There will be a medieval "Braunstein" April 17, 1971 at the home of Dave Arneson from 1300 hrs to 2400 hrs with refreshments being available on the usual basis.... It will feature mythical creatures and a Poker game under the Troll's bridge between sunup and sundown.” An eleven hour game session. One assumes that Greyhawk ran on a similar basis, at least on the weekends, and even on weeknights and for younger players at least 4 to 5 hours.

Given this disparity in time, both of the individual sessions and the length of campaigns, it’s very unlikely that the classic megadungeons of Greyhawk and Blackmoor, or even shorter published adventures like Tomb of Horror were approachable in shorter, less frequent sessions. In an interesting example, the 1975 Origins I run of the Tomb was supposed to be two hours, though famously only the a level “Evil lord” and 14 orc retainers played by Rob Kuntz finished it with a virtuoso display of calculating orc sacrifice that took 4 hours. This 1975 edition of the Tomb was lengthened for commercial release, with more complexity and puzzles added that greatly expanded play time.

Kuntz’s delve into the Tomb of Horrors varies from another aspect of early play that’s different from present conventions, Robilar the Evil Lord completed the Tomb of Horrors solo, with a large number of retainers. While there’s several stories of similar solo play or adventures for small numbers of drop in visitors, the party size that explored Gygax’s castle Greyhawk during it’s long weekend session ranged up to 10 or 20 players. As anyone who has run a group of that size can attest, organizational efforts and decision making take longer, but the party’s ability to handle threats (combat especially) are vastly improved. Contemporary, and especially online play, depends on smaller parties. Rime of the Frost Maiden, a recent WotC campaign, is designed for four to six players, compared with the six to nine players Keep on the Borderlands suggests.

While they overlap at the edges, and vary, all three of these circumstantial elements: campaign length, session length and expected party size are generally smaller in contemporary play. The limitations imposed by technology as well as different expectations of how rpg play will work have changed since the mid 1970’s. While none of these 2021 conventions are worse or better then those of 1976 they do militate for a different style of adventure design and perhaps rules modifications that account for shorter sessions.