Gary Gygax is probably the best known name in Role Playing Games -- still, nearly 15 years after his death. Considered Dungeons & Dragons’ co-inventor and principal author of most of its early material, “Uncle Gary” was also a tireless promoter of his game and of role playing games as a whole. For the hobby’s ½ century Gygax’s name has been synonymous with it, he shouldn’t need an introduction, but it's still worth taking a close look at his adventure design legacy. Specifically how Gygax designed his dungeon adventures.

Gygax was author of many of the best early adventures for Dungeons & Dragons including: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, Vault of the Drow, Village of Hommlett, Expedition to the Barrier Peaks, Tomb of Horrors and of course Keep on the Borderlands, likely the most played Dungeons & Dragons adventure of all time. While some of his adventures, such as Expedition to the Barrier Peaks and Tomb of Horrors, were at least significantly the work of others (Kask and Lucien respectively), though Gygax undoubtedly had a hand in them as well. His output was prodigious and his foundational adventures are still well known today. I’d argue that adventure creation, rather than rules of mechanics, was Gygax’s greatest strength as a designer. With Arneson, Gygax wrote a system of adventure or dungeon design into the 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons, but he didn't follow it long, and certainly not in his published work, instead innovating and diverging from his own early advice to pioneer a new style of adventure design. Yes, his most important contribution to the hobby was likely organization and promotion - and the hobby of role playing games owes him a great amount of credit, perhaps even its existence for his efforts there - but Gygax’s adventure design still stand tall a half-century later, and it's full of useful lessons and techniques.

Gygax & Design

Like all good designers, especially early in the hobby, Gygax’s design has its own flavor and concerns. For Gygax adventure design is most often focused on the nature of the forces opposed to the players and potential environmental factors or conflict among these enemies that the players can exploit. He was first a wargamer, and his signature adventures are far more “sieges” or “infiltrations” then they are “explorations”, though this is not universal or absolute. Gygax’s adventure writing itself is marked by an relative indifference to map design, and the use of sparse keys that offer the minimum of environmental detail while focusing on the monsters encountered and their military strategies or behavior.

Like all good designers, especially early in the hobby, Gygax’s design has its own flavor and concerns. For Gygax adventure design is most often focused on the nature of the forces opposed to the players and potential environmental factors or conflict among these enemies that the players can exploit. He was first a wargamer, and his signature adventures are far more “sieges” or “infiltrations” then they are “explorations”, though this is not universal or absolute. Gygax’s adventure writing itself is marked by an relative indifference to map design, and the use of sparse keys that offer the minimum of environmental detail while focusing on the monsters encountered and their military strategies or behavior.

Gygax designed a variety of scenarios over his long career, but the central challenge in Gygax’s best known adventures, at least the ones where he’s clearly the sole designer (again, not Tomb of Horrors or Expedition to the Barrier Peaks) is one of military tactics or strategy. In a Gygax adventure the party will succeed if they can outwit, destroy, suborn, or bypass a hostile, organized force more powerful than them. Examples of these forces include the giants in the Against the Giants modules, the humanoid tribes in Keep on the Borderlands, or the mountain giant and his flunkies in the Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun. In all cases the party is unlikely to survive a direct confrontation with the forces against them, and instead needs to use schemes, things they discover about and within the dungeon, or subterfuge to overcome them. Often these solutions require that the party access the enemy base/dungeon without alerting its guards, and then conduct a campaign of theft, assassination, and sabotage within.

The siege or infiltration scenario is natural enough, it’s the sort of thing that naturally evolves from skirmish wargaming -- where one wants to justify both a small group of characters and provide their player(s) agency within the context of a larger military conflict. In 2002, during a Question & Answer session on ENworld’s bulletin boards Gygax rejected idea that Dungeons & Dragons had an exact analogue to military siege scenarios, stating that “no actual D&D game module I've ever seen has taken the base, sieges, to the 'commando' raid stage, either in infiltrating a fortress of for breaking out of one to wreak havoc on the besiegers lines.” However, Gygax liked the concept, and claimed to be writing an adventure based on the scenario of infiltrating a fortress during a siege … his rejection of the idea appears more one of exacting terminology than to the suitability of the design itself. Setting aside the context of a strictly military “commando raid”, it’s obvious that Gygax often wrote adventures centered on infiltration as a part of a violent conflict - ambushes, evasion, assassination, and sabotage. While there are elements of dungeon exploration involved, including entire adventures written using other design forms, the infiltration scenario is distinct, and Gygax perfected it, even creating special tools to run it more efficiently.

When interrogating this style of design, the first thing to notice is that the primary source of tension in a Gygaxian Siege is not supply depletion or the pure risk of random encounters, but the larger risk of an alarm being raised. Once the fortress is alerted the adventure will change almost fundamentally as the enemy forces begin to actively patrol, reinforce each other and gather at choke points. A siege adventure is not usually a race against the steady depletion of character resources like the traditional dungeon crawl, but an effort to get as close to one’s goals before the alarm is raised and the enemy begins to hunt the party.

THE GUNS OF CASTLE GREYHAWK

Gygax’s most well remembered and signature adventures are to varying degrees "sieges" or infiltration. His adventure locales are then a variety of “Fortresses” that the party must infiltrate. This can be a subtle distinction, compared to exploration driven dungeons because many of the concerns for navigation are shared to a degree. As noted above, the distinction is best found in the central challenge faced by the characters, an this has a rippling effect that changes the entire adventure. In an exploration focused adventure the central challenge is navigation. The party seeks a path through the dungeon that limits risk and provides the most rewards. In an infiltration, the characters are almost immediately confronted by one or more groups of organized foes who guard access to rewards, either the best treasure, or more often the explicit goal of the adventure, and overcoming these foes is the central puzzle.

To highlight this distinction, consider the Gygaxian Fortress’ fictional influences -- most obviously “commando films” like the 1961 movie Guns of Navarone. In a Gygaxian Fortress the party is tasked with entering and destroying or stealing from some sort of well defended location, home to a powerful hostile force. Shockingly this is also a description of the plot of Guns of Navarone -- an enormously successful film adaptation of the action novel by Allistair MacLean, a British WWII naval veteran. The movie follows a commando team sent to destroy a pair of German super guns on a small Aegean fortress island (complete with ruined classical temples, a castle-like ancient fortress, and underground bunkers - a multi-level mega dungeon of sorts…)

Made up of a variety of specialists, dubious war heroes, and partisans, the commando team is a collection of dark pasts and internal conflicts. This setup is shared with the related heist/crime genre, and often finds its way into Western genre as well, especially the Western plotline of the “cavalry story” and “outlaw story” - all three genres of course contribute a fair bit to RPGs. As their adventure continues the commandos use disguise, schemes, an alliance with local partisans, and of course a lot of bloody, vaguely superhuman, violence to overcome and trick the island’s defenders, accomplishing their mission against an evil foe while losing several of their number.

For cinefiles a notable aspect of Guns of Navarone, and the “Commando film” in general, is how the genre breaks from the war movies of the 1950’s, which were fundamentally more realistic -- likely because the earlier movies’ audience, actors, and producers were expected to be more familiar with the realities of WWII. Commando films were part of the movement towards modern action movies, where the heroes ultimately become than just tough or skilled soldiers and begin to take on super heroic or mythical aspects. Modern Superhero cinema, 1980's Action movies and Commando films are all part of this lineage, though the heroes powers in the Commando film are still at the edge of human ability. In Commando films the protagonists don’t have the abilities of John Wick or Rambo, and filmic commandos lack the near invincibility of these modern Action heroes, let alone Superheros … bullets can easily hurt, kill, and incapacitate a commando hero. The heroes of Guns of Navarone still need time to recover from injury, and die rather frequently by the standards of modern adventure cinema. Nor do Commando films in the 1960’s and 1970’s follow an individual protagonist as much as the team as a whole, which allows for some, maybe most of its members to die or fail.

Popular fiction genres and RPGs of course interact, and early Dungeons & Dragons characters are a lot like the characters in Commando films -- it’s not realism exactly, and it draws from pulp heroes like the Grey Mouser and John Carter, but the genre still relies on characters who aren’t dramatically more powerful then normal humans, and the story can have multiple protagonists - like an early RPG party rather than a singular hero. Older games are a lot more like older movies and genre fiction, while the characters in newer ones share a lot with the contemporary action hero.

Recognizing The Guns of Navarone and the Commando film as a fictional basis for many of Gygax’s adventures offers insight into specific design choices that Gygax makes again and again, despite his own partial dismissal of the analogy. To better understand the Gygaxian Fortress as a dungeon design form, the types of challenges found in Commando films (and even heist movies) is useful. To look at the connection more closely and how it functions as a RPG It’s worth examining some of Gygax’s better known adventures, including: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun, and Keep of the Borderlands. All of these adventures require commando raids or infiltrations if the party is to survive and they adapt many of the scenes or elements common in commando cinema.

Besieging the Gygaxian Fortress

To highlight this distinction, consider the Gygaxian Fortress’ fictional influences -- most obviously “commando films” like the 1961 movie Guns of Navarone. In a Gygaxian Fortress the party is tasked with entering and destroying or stealing from some sort of well defended location, home to a powerful hostile force. Shockingly this is also a description of the plot of Guns of Navarone -- an enormously successful film adaptation of the action novel by Allistair MacLean, a British WWII naval veteran. The movie follows a commando team sent to destroy a pair of German super guns on a small Aegean fortress island (complete with ruined classical temples, a castle-like ancient fortress, and underground bunkers - a multi-level mega dungeon of sorts…)

Made up of a variety of specialists, dubious war heroes, and partisans, the commando team is a collection of dark pasts and internal conflicts. This setup is shared with the related heist/crime genre, and often finds its way into Western genre as well, especially the Western plotline of the “cavalry story” and “outlaw story” - all three genres of course contribute a fair bit to RPGs. As their adventure continues the commandos use disguise, schemes, an alliance with local partisans, and of course a lot of bloody, vaguely superhuman, violence to overcome and trick the island’s defenders, accomplishing their mission against an evil foe while losing several of their number.

For cinefiles a notable aspect of Guns of Navarone, and the “Commando film” in general, is how the genre breaks from the war movies of the 1950’s, which were fundamentally more realistic -- likely because the earlier movies’ audience, actors, and producers were expected to be more familiar with the realities of WWII. Commando films were part of the movement towards modern action movies, where the heroes ultimately become than just tough or skilled soldiers and begin to take on super heroic or mythical aspects. Modern Superhero cinema, 1980's Action movies and Commando films are all part of this lineage, though the heroes powers in the Commando film are still at the edge of human ability. In Commando films the protagonists don’t have the abilities of John Wick or Rambo, and filmic commandos lack the near invincibility of these modern Action heroes, let alone Superheros … bullets can easily hurt, kill, and incapacitate a commando hero. The heroes of Guns of Navarone still need time to recover from injury, and die rather frequently by the standards of modern adventure cinema. Nor do Commando films in the 1960’s and 1970’s follow an individual protagonist as much as the team as a whole, which allows for some, maybe most of its members to die or fail.

Popular fiction genres and RPGs of course interact, and early Dungeons & Dragons characters are a lot like the characters in Commando films -- it’s not realism exactly, and it draws from pulp heroes like the Grey Mouser and John Carter, but the genre still relies on characters who aren’t dramatically more powerful then normal humans, and the story can have multiple protagonists - like an early RPG party rather than a singular hero. Older games are a lot more like older movies and genre fiction, while the characters in newer ones share a lot with the contemporary action hero.

Recognizing The Guns of Navarone and the Commando film as a fictional basis for many of Gygax’s adventures offers insight into specific design choices that Gygax makes again and again, despite his own partial dismissal of the analogy. To better understand the Gygaxian Fortress as a dungeon design form, the types of challenges found in Commando films (and even heist movies) is useful. To look at the connection more closely and how it functions as a RPG It’s worth examining some of Gygax’s better known adventures, including: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun, and Keep of the Borderlands. All of these adventures require commando raids or infiltrations if the party is to survive and they adapt many of the scenes or elements common in commando cinema.

Besieging the Gygaxian Fortress

At the center of the siege scenario, or the Gygaxian Fortress, is a powerful organized enemy who controls the Fortress or the majority of it. This may seem a departure from many other Dungeon Crawl design forms where faction intrigue is a or the major engine of play, but Gygax often maintains faction intrigue by adding factions in the form of prisoners, rivals, or the dissatisfied elements of the primary antagonist's forces. The initial appearance of a location is as one fully defended against outsiders however, and this has a use: it informs the party that they can’t expect to easily enter the dungeon through its most obvious access points and begin a search for treasure. To succeed the party must avoid detection by the fortress inhabitants who are collectively more powerful than the party, but weaker when unaware and distributed.

The dungeon as an active location with a unified foe is the undergirding structure of the Gygaxian Fortress and what makes it a distinct form, different from other dungeons. The adventure offers a foe who is likely too powerful for the party to confront head-on and instead the players seek to both weaken that foe and reach their goals without starting a set-piece battle. This usually involves infiltration, avoiding raising the alarm, but much like a well nuanced understanding of the OSR maxim that “combat is a fail state”, combat and triggering the alarm are inevitable, even if undesirable … the players’ luck eventually runs out and the fortress will rise against them. With the alarm raised the players’ experience of the adventure shifts. It loses any exploration elements and becomes a dramatic race or running battle. As the enemy marshals and begins to hunt the party, the players have to decide to push on to their goal, make a stand, or flee to safety with whatever they have achieved. The success of any of these plans will be largely determined by the amount of sabotage, planning, and assassination that the party has accomplished before the alarm.

This structure effectively builds a climax into the scenario, likely a big final battle even, though players must always act to make this stage of the adventure favorable to the party through a variety of commando-like schemes: eliminating patrols, assassinating leaders, sabotage, preparing the battlefield, finding local allies and preparing escape routes. To make such a complex scenario work consistently, especially as a published adventure for others to run isn't just a simple matter of keying up the dungeon printing it off for others to run though. Like all design forms, there are ways to encourage a certain kind of play, or at least ways to make it easier for referees to run them, and reward players who engage in them.

PLAY IT LIKE A WARGAME

The most notable and clearly delineated of the Gygaxian Fortresses’ innovations or tools, and one generally applicable to other dungeon design forms, is the “Order of Battle”. An Order of Battle is a list of a faction or area’s hostile inhabitants including a variety of information: statistics, initial location, how long they take to respond to alarms, their tactics and how they will respond to various events.

While almost an essential part of any war game scenario, they are rare even now in RPG scenarios, though Gygax started experimenting with this design as early as 1978’s G1 - Steading of the Hill Giant Chief. The Order of Battle is extremely limited, specific to a single location, and fails to address issues like if and how long any surviving guards and pets in the Steading will take to respond to the Chief’s shouts or the sound of battle, but it is clearly an Order of Battle. It is designed to offer a referee an accessible format that will help run a tactical combat encounter and contains a list of a few of the essential elements of a more complex Order of Battle, specifically the area’s defenders’ immediate locations (though these could be better marked on the map as well), and a schedule of their HP. The key also includes one special tactic that the giant chief will use (his ballista/crossbow).

Over time Gygax’s use of Orders of Battle becomes more complex and improves. By 1982’s Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun Gygax is comfortable including two complex Orders. The first is for a cavern full of orcs and the second, far more expansive Order covers the adventure’s main location, the forgotten temple. In addition to the breakdown of forces it takes three pages to describe when the defenders will arrive and from what locations and offers notes on how the temple residents will respond to raids, what happens if they flee in defeat, and how they will be reinforced. Gygax also lists both the dungeon’s normal patrols (random encounters) and how they change after any encounter with the party. An Order of Battle like this is an amazingly useful resource for the referee who wants to run a large organized faction as it lays out and keeps all the resources and tactics of an antagonistic faction on a single reference sheet. Not only does it make running a mass combat or repeated raids easier, it also emphasizes to the referee that the monsters are organized and will only remain hidden in their individual lairs waiting to be killed under circumstances where their coalition is destroyed and they are forced to flee.

While the second Order in Forgotten Temple is more extensive and informative, the first, for the “Valley of the Orcs” is notable in that it forms entire entry beyond notes about the orcs red and yellow heraldry, a map of their rather extensive caves (no key is offered), and a single line covering their treasure (a coin hoard in a chest) and noncombatants (including 120 defenseless orc babies). The encounter with the Jagged Knife Clan of Orcs appears as an almost entirely a tactical one, but in typical Gygax manner the orcs and have evicted a lamia from its cave and are now in a sort of guerilla war with the cat monster and its pack of leucrotta. Even these two fairly limited encounters dropped on Forgotten Temple’s overland map offer an opportunity for more then pure combat because suddenly there is the possibility of faction intrigue and for the characters to build relationships with either the lamia or the orcs, both of whom could be potential allies against the larger threat of the Mountain Giant and its Norker band (though I suspect both would want treasure for such risk, even with the party having killed off their rivals).

Beyond the useful tool of the Order of Battle, Gygax often provides a few other elements to better integrate infiltration and faction intrigue into his scenarios. These both purely map design elements that either make a tactical situation more interesting or allow the party clever ways to bypass strong points, but they also include various opportunities to assassinate or sabotage the foes within the fortress. B2 - Keep on the Borderlands has several such map elements, includes examples of the former, primarily secret doors that connect many of its factions’ individual cave lairs. The “forgotten room” between the two orc lairs offers a good example allowing a party that has invaded one of the orc lairs to access the leader of the other almost immediately after finding the secret door and potentially removing the second group’s leadership. Other secret doors allow access to the bugbear gang leader’s cave, provide access to the hobgoblin leader’s hidden rooms (including access from the far easier to infiltrate goblin lair), grant a hidden way into the temple of chaos and from the ogre’s lair to the goblin guardroom (and facilitate the goblin’s use of the ogre as a mercenary).

Similar map based tools to facilitate infiltration include roof or window access, such as the ability to descend into the courtyard of the steading in G1, and castle infiltration classics like secret postern gates or drainage channels that lead to a dungeon level. Even entire forgotten or abandoned sections of the dungeon (also found in G1) that can allow characters to create hideouts within the dungeon or lead to secret entrances. Beyond this kind of feature, Gygax’s maps are not usually very large or especially full of interconnections, but they, and the placement of specific areas within them do have an internal logic … they make sense, especially when one looks at them from a defensive or military perspective. There are guardrooms that watch entrances, areas where the humanoids that invariably defend Gygax’s dungeons can muster for a larger battle, living quarters and armories. This is also part of the Fortress design sensibility, the infiltrating players should be able to learn enough to guess where they are within the dungeon and what might be nearby. When one looks at the map of the hill giants’ steading in G1 it has four distinct areas: a central hall and yards, a cluster of buildings on the Eastern/left side where the giants live, and a barracks and armory in the North East. The Western or left side of the map is another jumble of buildings that contain servants, guest rooms, kitchens, and other functional spaces. Even the dungeon level of the steading is largely that, a dungeon where the Giants trap their orc slaves. The steading may be a fantastical space and even throws in some oddities in the dungeon level, but overall it makes sense. One won’t stumble from the kitchens directly into the chief’s chamber.

Gygax’s dungeons are usually like this, spaces whose layout the players can learn or anticipate, and this makes for a better infiltration scenario. Players can make plans to assassinate leaders in their quarters, sabotage the armory, barricade the barracks door, poison supplies in the kitchen, or free prisoners because the location is laid out in a more or less sensible manner. Players will take advantage of these opportunities, and one can see opportunities to weaken the overall force of the giants in G1 throughout. I know of players doing the following schemes with a variety of success: blowing the horn to sound an alarm and drawing the feasting giants into traps, sneaking into the kitchen store rooms to poison the giants’ feast, sabotaging the giant’s armory, charming the giant’s pack of dire wolves and then letting the giants call them - turning them on their keepers, freeing the orcs below, and of course setting the whole place on fire.

Gygax also expands on these map based opportunities with specific situations that provide opportunities to undermine his fortresses. In G1 we even have opportunities spelled out in the very sparse text: the party can steal the clothing of young giants and disguise themselves, negotiate with various dissatisfied maids, servants, and slaves for information, treasures or alliance, and the party can ambush individual giants such the numerous drunken guards or a “handsome giant warrior” who wants to show off in front of the giant maids in the servant’s quarters and will not call for help. Designing the Gygaxian Fortress is more than simply setting up a war game scenario, though this is part of it, it’s creating a space that offers opportunities and clearly defined for player actions and schemes and doing so with a variety of tools.

Gygaxian Naturalism

No discussion of Gygax’s design could be complete without reference to another of its key attributes, one that also adds to the functionality of his adventures -- “Gygaxian Naturalism”. The phrase was first widely discussed and defined, as with many OSR concepts, on James M’s blog Grognardia and means more or less a loose ecological or logical approach to RPG setting building. In the 2008 post, James M defines it as “[The] tendency, [...] to go beyond describing monsters purely as opponents/obstacles for the player characters by giving game mechanics that serve little purpose other than to ground those monsters in the campaign world.” James cites examples such as monster spells and abilities that have little or no effect on gameplay, and the long controversial inclusion of non-combatant humanoids in their lair creation process.

In an earlier post, Gygax’s naturalism also had an aesthetic aspect for James, found in the way the Monster Manual depiction of Orcus has elements of Medieval art and a less glossy or cliched appearance than the then new version on the cover of 4th edition’s Monster Manual. There’s an element of both functionality and aesthetics to Gygaxian Naturalism - it is both the grounding interconnectedness and understandability of Gygax’s worlds and his specific aesthetic. Gygax’s own aesthetic can perhaps be described as Osprey Publishing’s books on historical armies spiced with Tolkien and other mid-century fantasy and sci-fi authors.

This aesthetic is a good fit for Gygax’s adventures and does add to their playability because it allows a player to obtain a useful genre mastery of both the historical elements and much of the fantastical. Knowledge of medieval polearms provides a player with the option of using the hook on their bill guisarme to collect things from magical pools while reading Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions will give players knowledge of Gygax’s trolls and their weaknesses. The grounded element of Gygax’s aesthetic -- it’s “gritty” military or wargame armor and weapon variety helps place his adventures firmly in the “heroic” rather than “superheroic”. Again this reflects the way Gygaxian adventures match the tone of the 1960’s Commando film where the realism of the military aspects limit the super heroic aspects of the story and heroes. In Guns of Navarone’s climax the commandos have lost most of their explosives and must set a trap using the gun’s own ammunition - this sort of complexity can be compared with the less rigorous approach of more modern Action films (or even more video games), where large guns and vehicles are often destroyed by a single fragmentation grenade. The “realism” of the Commando film, while still stretched, dominates because weapons operate with predictable limitations, rather than as metaphors.

While Gygax’s aesthetic helps his adventures function, grounding players in concerns about equipment and imposing the same sort of stretched realism. This effect may fade as level increases and magic items and spells whose effects are far more metaphorical become common, but the grounding never entirely goes away. It's a great trick, and it isn't necessary to use either the same set of inspirational fantasy or inspirational history as Gygax to replicate the effect. References allow helpful because they grant players a way of grounding the world and give referees tools to better extrapolate detail and can be borrowed from whatever history one finds convenient (e.g. a warrior wearing a buff coat will likely have a lobster tail helmet will likely have a basket hilted saber for example), and as long as the references are accessible, they can serve as a source of detail and grounding for the game. References and accessible knowledge about the fantasy world are the real heart of Gygaxian Naturalism - what makes it function as a design tool because it's largely about forming an interconnection between elements of the adventure or setting and useful detail that players can discover and referee can extrapolate from. Borrowing from other, richer sources takes a lot of the load off of the adventure itself to provide detail.

Gygax himself never uses the term “Naturalism”, but comes close in his discussion of setting design in the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide and it has little to do with aesthetic or tone of Gygax’s adventures, instead he cautions that “Dungeons [and wilderness] must be balanced and justified, or else wildly improbable and caused by some supernatural entity which keeps the whole thing running - or at least has set it up to run until another stops it. In any event, do not allow either the demands of "realism" or impossible make believe to spoil your milieu. Climate and ecology are simply reminders to use a bit of care!” Following this, Gygax provides some examples of fantastical elements that could allow a setting with so many monstrous predators to make some kind of ecological sense and warns that players may demand to understand the world, but advise that the referee shouldn’t go too far attempting to simulate reality.

Gygaxian Naturalism isn’t just a way of visualizing a game world, in Gygax’s adventures it serves to ground the fantastic space by making it coherent and comprehensible. The hill giants' steading has kitchens, storage spaces, barracks, and other rooms one would expect in a fortified hall, with the other creatures encountered in the place are either servants (orcs, bugbears, and ogres), pets (dire wolves, a bear, manticores), vermin (troglodytes, giant lizards) or visitors (the cloud giant). Gygax goes further in The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth (1979):

“The pools support small, pale life—crayfish and fish, as well as crickets, beetles and other insects. Characters who listen closely will hear a number of small sounds, mostly those associated with the insects and other small life which inhabit the caverns. [... The caverns are also home to] bats, a few giant rats, many normal rats, huge nightcrawlers (3' to 6' long, no attacks), or various large-sized slugs and grubs. All are harmless. These are the usual prey for the larger creatures inhabiting the caverns.”

These two examples, I think of them as the giant’s cookpot and the huge nightcrawler, perform two distinct services to the referee and players, both of which are part of Gygaxian Naturalism. As mentioned above the cookpot sort of detail offers the party tools for unorthodox approaches to victory. The next meal for the majority of the giants is accessible. It is available to the party as a way to poison the majority of the giants (which of course many would successfully save against), but the giants' kitchen also represents a potential tactical advantage to a party that uses disguise to enter the main hall carrying something dangerous and pretending it’s the next feast course. A party might emulate the bugbears in the Caves of Chaos and offer skewers of meat, using the skewer as a weapon in a last minute sneak attack. A giant sized pot of stew (or hot oil pretending to be stew) is also a potential weapon. While few of these possibilities are described, though specific items such as potions of poison and delusion as well as dark elf wine that compels even the giants to drink to drunkenness are available, having kitchens and storerooms in the giants steading provides them as a matter of simple deduction and thought by the players. They are available because every person knows what might be in a kitchen and can imagine how one might use food and kitchen supplies to cause mayhem.

The "nightcrawler" example is less immediately accessible in game, but it is still potent. By offering a fantastical ecology for the Lost Caverns Gygax has given the referee tools for description and explanation -- a sense of what happens in the depths when the characters aren’t there with monsters hunting worms and nibbling at strange mushrooms in the dripping darkness. As simple as these ideas are, they make it easier to describe spaces and the activities of the dungeon’s inhabitants. They offer clues to answer the sorts of questions players routinely ask: “What’s in the ogre’s pocket” or “what are the goblins doing”? While not immediately gameable they encourage gameability because they provide continuity and give accessible details to the fantastic space.

Keying For Conflict

Beyond the general design techniques and specific tools or scenarios, Gygax’s keying is also focused on building a fortress for siege and infiltration. Fundamentally this means focusing on enemy/monster organization, behavior, and tactics in his keys, while adding just enough environmental detail to sketch a space. Gygax’s keys, are sparse where they describe spaces, but grounded in exact physical description: dimensions, basic materials, and especially notable features. These are usually sufficient, as Gygax also had a knack for providing a line or even a few evocative adjectives that give a referee enough to work with in the context of the adventure.

This description of “the Mound of the Lizardmen” in Keep on the Borderlands is a good example of Gygax’s typical approach:

“The streams and pools of the fens are the home of a tribe of exceptionally evil lizard men. Being nocturnal, this group is unknown to the residents of the KEEP, and they will not bother individuals moving about in daylight unless they set foot on the mound, under which the muddy burrows and dens of the tribe are found. One by one, males will come out of the marked opening and attack the party. There are 6 males total (AC 5, HD 2 + 1, hp 12, 10, 9, 8, 7, 5, #AT 1, D 2-7, MV (20’) Save F 2, ML 12) who will attack. If all these males are killed, the remainder of the tribe will hide in the lair. Each has only crude weapons: the largest has a necklace worth 1,100 gold pieces.

In the lair is another male (AC 5, HD 2 + 1, hp 11, #AT 1, D 2-7, Save F 2, ML 12) 3 females (who are equal to males, but attack as I + 1 hit dice monsters, and have 8, 6 and 6 hit points respectively), 8 young (with 1 hit point each and do not attack), and 6 eggs. Hidden under the nest with the eggs are 112 copper pieces, 186 silver pieces, a gold ingot worth 90 gold pieces, a healing potion and a poison potion. The first person crawling into the lair will always lose the initiative to the remaining lizardman and the largest female, unless the person thrusts a torch well ahead of his or her body.”

This is a longer example of Gygax’s early and best known style of keying, though it describes an entire lair/location with reference to a simple map. It should be obvious that the primary focus here is on the combat or tactical potential of an encounter with the lizardmen. Reading a single paragraph we get the lizardman band’s: makeup (7 males, 3 weaker females, and 8 children), behavior (“evil”, nocturnal, predatory, and territorial about their mound), battle tactics (individual emergence and attack of the warriors, the dangerous tunnel ambush of the mound dwelling male and females), and a potential counter to this dangerous tactic (caution and fire).

The Lizard Mound (and the “lizardmap” that completes the key) shows Gygax’s primary concern is for tactical combat, but the description of the lizardman mound still contains a few useful details for the referee to work with. Descriptive element consists only of the notes that: (1) the mound is in a fen of streams and pools, and (2) the lizardmen dwell in the mound of muddy burrows and dens. As simple as it is, this description is likely enough to goad the referee’s imagination and create a larger descriptive scene - for example:

“a mound of black raw earth rising from the marsh, denuded of the lilies and reeds that fill the surrounding pools, and pocked with narrow dark holes, leading inward to narrow tunnels, half flooded and stinking of rotten swamp plants, urea, and dead fish.”

This kind of basic description is easy to reach for with this sort of space, and works in the context of Keep on the Borderlands earthy vernacular fantasy, it’s also somewhat limited. Neither the Lizardmen themselves or their treasures are meaningfully described. The only description of these creatures is of their “exceptionally evil” nature, a difference from the standard “neutral” lizard man (who still enjoys “feasting” on people) as described in Moldvay Basic (which was likely written after B2). However Basic Dungeons & Dragons description of Lizardmen as “water-dwelling creatures [who] look like men with lizard heads and tails” is likely to have been informed by Gygax’s conception of them here -- it’s excluded from both Greyhawk and the AD&D Monster Manual where no physical description is offered, though the desire to eat people is noted in both places and image in the Monster Manual is more than sufficient.

Again, across Gygax’s writings, he emphasizes the behavior, demographics and mechanical statistics of the foes. With the lizard men this works well enough -- the name alone describes them rather well and it’s easy for a referee who needs more description to pull from their own common knowledge of lizards. When I first played B2 in 1983, the twelve year old running the game was familiar with anoles and so our lizardmen were green and brown, with tiny scales, long narrow heads, and throat sacks. Presumably at another table they were iguana based or jagged toothed dinosaur people. By focusing instead on the tactics, culture (as much as feasting on people or sometimes living in huts is culture), Gygax centers his game design around combat and negotiation with his monsters, especially his “humanoid” monsters, who generally receive longer write ups. In Gygax’s less compelling work this tendency towards a sort of shallow military sociology expands, perhaps excessively, and sometimes in ways that create a sort of absurd taxonomy or racial essentialism that has been the subject of much critique. In the context of Gygax’s best works however, especially in adventures where he is presenting singular encounters without extraneous social commentary, it is good design and hard to find objectionable.

The focus in these adventures is on the most likely encounter the players will have with the “monsters”. Often, such as at the Lizard Mound, this is combat -- a violent altercation, proceeding first through near ritual combat, and then a horrific ambush in the muddy tunnels below - likely a fatal encounter for a low level party. Yet Gygax has given us enough about lizardmen and their lair here in a short paragraph, and in the supporting text of Moldvay Basic (or AD&D if one was playing an early edition of B2) to give referees some support for other possibilities. The lizardmen want to eat people but also value treasure, speak their own language, prefer to hunt at night and by ambush, and have some sense of ritual and honor (hence the challenge style attack on trespassers). There are possibilities for negotiation, and of course betrayal - being stalked by murderous nocturnal lizardmen with a penchant for eating people. It’s enough that even this simple, one paragraph wilderness encounter, nearly free of description, could be used as the bedrock of a regional faction should unlikely events occur in one’s game.

Where Gygax’s style suffers is when it expands too far, such as the pages’ long description of the Drow in Vault of the Drow. The dry and tactical about equipment and troop types would be better included in adventures and related to specific encounters with drow, and it becomes messily intermixed with details about the drow’s matriarchy and simplistic fairy-tale like history of drow society. Similar breakdowns occur when Gygax must describe stranger spaces, such as the subterranean fairyland the drow inhabit. While there are some sound descriptions of places like the Drow capital, Gygax attempts to maintain the style of his tactical and referential descriptions, but expands them and mixes in complex prose, often resulting in a key that’s still functional, but loses the accessibility found in his best work.

These lower quality keys are still functional, but also often insufficient and yet somehow excessive because they focus on minutia (such as a list of the many fungus forms found along the road to the Drow capital or the way that the glowing gems in the underground vault’s ceiling function.) When not listing minutia, Gygax’s longer keys rely on generalizations rather than details, and where they don’t tend to use empty adjectives to make up what’s missing. For example, in Vault of the Drow one of the rooms within the Spider-Goddesses’ temple is described with this: “The bed chamber of the High Priestess is lewdly and evilly decorated.” While it’s possible to argue that by emphasizing the “lewdness” and “evilness” found in Drow theocracy’s decorative aesthetics, rather than describing specific objects, allows a referee can fill in the details that their table will find most evocative of lewd evil, this is a stretch, especially compared with the way the Lizard Mound’s muddy tunnels and fen bring out an immediate image. Yet this loss of meaning and descriptive detail isn’t simply an issue in Gygax’s later or higher level works, it’s not a problem of pulling back the descriptive lens or writing an adventure on a grander scale. 1982’s The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun is both a higher level adventure (5th - 10th) and one with a range of locations … but it manages to follow the pattern of simple and robust description of clearly defined spaces. Forgotten Temple generally uses concrete descriptive elements that evoke pulp literary standards. Rooms are filled with nests of “old clothing, cloth, rags, and leaves” or “a battered armoire [...] with one door missing, but its drawers still intact”. Doors are “slabs of ancient bronzewood” and the walls have nauseating veins of plum-colored and lilac stone. Gygax’s descriptions seem to become less useful and harder for the referee to grasp to the degree that they describe novel or complex spaces. I believe this is because exploring the space itself is less important to his design philosophy than encountering its inhabitants, the first will always give way to the second, regardless of the most likely way the location will be used. This is not a terrible way to design dungeon crawls … and it can have interesting effects, but it is neither the only way or always an immediately useful one.

The Gygaxian method of designing by focusing largely on the tactics and military structure of the creatures in his adventures tends to struggle not just with complex description, but with complex situations, such as the party’s infiltration of the Drow city. Locking onto the combat potential and tactics of the potential adversaries when combat is not the most obvious or likely result, does the opposite of the Lizard Mound’s description and impedes the most likely variety of play. Perhaps it’s possible to say that location based keying … while it must always describe the area, any inhabitants, and what it contains (traps, dressing, treasure, secrets) … should focus on or highlight whatever is most likely to occur there. In the context of describing the Drow city in Vault of the Drow this isn’t direct conflict, but negotiation and subterfuge.

Despite these critiques, and missteps at keying complex situations and locations (and to be fair such things are hard to write), it’s worth noting that Gygax’s adventure keys almost always offer sufficient, playable, and reasonably succinct description. While Gygax’s approach focuses on the “war game” possibilities of the space or encounter this is always usable information because direct conflict is always at least a secondary possibility, and Gygax rarely omits other information entirely.

This means that are far worse ways to key a dungeon than Gygax’s wargamer method because letting a referee know what to expect from monster encounters will always be a key aspect of designing dungeons, but it is best for a certain type of location based adventure that I call a “Siege”. Siege adventures focus on infiltration of and confrontation with hostile organized forces. They tend to be locations where there is one controlling faction who is at odds with the party. The besieged faction is almost always too powerful for the party to safely confront in direct combat, so instead the party must use commando tactics to destroy them in detail. Siege adventures and Gygax’s design form tend to push the adventure into tactical combat and disfavor, though don’t eliminate, other aspects of dungeon crawling such as exploration. Given how key a figure Gygax’s is to the evolutions of Dungeons & Dragons and this aspect of his creative vision it’s easy to see how the game has increasingly focused on increasingly complex tactical combat through its passing editions. Of course since Gygax’s design is largely from the early era of the hobby, he is not as focused on combat as much contemporary fantasy RPG design. By today’s standards Gygax’s adventures are exploration and negotiation focused, but compared with some other early design dungeon design philosophies, such as Jaquays’ and perhaps Arnesons’ design, Gygax’s design sensibilities are directed at combat and tactics. While I don’t attach any blame to Gygax for it, Gygaxian Fortresses and their focus on tactics, especially when filtered through tournament design and the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons system designed to support it planted the seeds for the “Adventure Path” as a string of tactically complex set piece encounters - the dominant form of Dungeons & Dragons adventure design since the 1980’s.

War Exhaustion

While Gygaxian Fortresses are undoubtedly a successful and compelling design form they are somewhat limited, and from the beginning players and designers have sought alternatives. Even Gygax wrote (or adapted) other kinds of adventures - Tomb of Horrors for example is a puzzle dungeon. The Gygaxian Fortress emphasizes a single scenario - combat against an organized foe, and while it has room for exploration and other aspects of classic play, it will always primarily lead to combat. Combat of course requires some sense of balance between the forces to work as a game, though most of the tricks and tools the Gygaxian Fortress uses are about making sure the players have ways of rebalancing a scenario where the mechanics of direct combat greatly disfavor them. The availability of balancing factors or tools within the Gygaxian Fortress is the essential feature of the “Combat as War” concept, named and well described in a 2012 EN World Post, the basic idea is that in older editions or play styles of Dungeons & Dragons, the players’ goal in combat is to find ways to triumph over more powerful enemies through trickery and optimal use of setting aspects: ambushes, monster weaknesses, betrayals and taking advantage of geographical features to avoid “fair” combat.

It should be obvious that the idea of characters avoiding combat to “win” is not a primary Gygaxian concern. While Gygax’s design certainly encourages “Combat as War” … the more recent “Combat as a Failstate” is a later OSR concept. “Combat as a Failstate” is an interpretation of design developed on the player side of the table, perhaps as the result of trying to play through Gygaxian Fortress scenarios with the smaller parties common to later editions (3-6 “heroes”), rather than older module’s suggested 6 or more characters, plus henchmen. While, like “Combat as War” the theory around it comes out of the 2010’s and the OSR, the problem is older.

Parties of 3 or 4 PCs weren’t uncommon back in the 1980’s either … they may have been even more common then, given the lack of online play. Faced with the same balance issue as OSR groups approaching adventures designed for large parties with smaller ones, and as always trying to keep their characters from dying, early fans also sought ways to allow smaller parties to confront the larger groups of enemies provided in Gygax’s scenarios and rules. The “pre-OSR” answer to this issue -- described as early as 1975 in the Alarums & Excursions fan magazine, and leading to the “Dungeons and Beavers” culture of Cal-Tech/the Western US -- has been to borrow from fantasy fiction and to increase character survivability and power. Eventually this evolves into the “Trad” style of games and curated encounters with a greater concern for both narrative necessity and survivability. This design solution eventually informs or even defines subsequent editions of Dungeons & Dragons (including those developed by Gygax, whose AD&D characters are far more powerful and resilient then 1974 OD&D’s) until it evolve into design elements like “CR” and adventure forms like the “Adventure Path”.

Turning its back on “Trad” design, at least to a degree, the “OSR” solution since at least the mid-OSR has been two-fold. First, a vague gesture at “system mastery” and insistence on playing things as written in older modules (large parties). Second, adoption of the idea that combat should be avoided when possible and that players should seek it only when necessary and on the most advantageous terms -- “Combat as a Fail State”. One can of course add a third solution, something I’ll call “The Sacrament of Death” after Eero Tuovinen’s essay. The “Sacrament of Death” solution is to design for and create player expectations of frequent and messy character death. While Tuovinen draws it from player complex 90’s “Trad” games and incorporates ideas from the Story Game play style and community, the idea of treating character death as inevitable and fun is found in some corners of the Post-OSR as well with games like Mork Borg and the story/OSR hybrid Trophy Dark.

The primary OSR solutions to the problem of combat lethality and party size mismatches is to reemphasize “Combat as War”, and play with large parties of characters and the expectation of higher lethality. Sadly this solution is rarely championed in a positive or thoughtful way, as the leaders in this space tend to simply deny the existence of any issue, while passing moral judgment on tables where it applies. This is often presented with all the toxicity, hate mongering and creepiness common to the bad parts of the larger “gamer” community, and its “theory” limited to homophobic insults and the phrase “Get Good”.

Still exploring “Combat as War” is a viable solution when one acknowledges the limits of Gygax’s early design and works to create a campaign that builds on the potential for high character lethality and need for large parties. Such games include both accepting physical libations, such as the need for a larger player base and “stable” of characters, plus more modern innovations or extrapolations of older ideas such as “1:1 downtime” and renewed interest in “Braunstien” style campaigns. With these tools and expectation setting this style can work very well at conventions and games stores, or when one has a large group of players without the normal adult conflicts of work and family. It still doesn’ address the problems for smaller tables, just as the wargame and later tournament style of design didn’t address them in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and that is fine.

The “Combat as a Fail State” solution to smaller parties and high lethality is different, asa it supposes that asymmetrical encounters exist with the expectation that parties aren’t supposed to confront them (and certainly never head-on). In its most complete form it creates a new style of adventure design, a holistic reimagining of dungeon crawl adventures for smaller parties. The individual solutions involved in this process are the innovations of the mid-OSR, from roughly 2012-2017, but still find roots still in Gygax’s Fortresses, or at least are influenced in the negative by struggles with it. For an example of this, and the limits of the Gygaxian Fortress, one can look to B2 - Keep on the Borderlands.

The dungeon as an active location with a unified foe is the undergirding structure of the Gygaxian Fortress and what makes it a distinct form, different from other dungeons. The adventure offers a foe who is likely too powerful for the party to confront head-on and instead the players seek to both weaken that foe and reach their goals without starting a set-piece battle. This usually involves infiltration, avoiding raising the alarm, but much like a well nuanced understanding of the OSR maxim that “combat is a fail state”, combat and triggering the alarm are inevitable, even if undesirable … the players’ luck eventually runs out and the fortress will rise against them. With the alarm raised the players’ experience of the adventure shifts. It loses any exploration elements and becomes a dramatic race or running battle. As the enemy marshals and begins to hunt the party, the players have to decide to push on to their goal, make a stand, or flee to safety with whatever they have achieved. The success of any of these plans will be largely determined by the amount of sabotage, planning, and assassination that the party has accomplished before the alarm.

This structure effectively builds a climax into the scenario, likely a big final battle even, though players must always act to make this stage of the adventure favorable to the party through a variety of commando-like schemes: eliminating patrols, assassinating leaders, sabotage, preparing the battlefield, finding local allies and preparing escape routes. To make such a complex scenario work consistently, especially as a published adventure for others to run isn't just a simple matter of keying up the dungeon printing it off for others to run though. Like all design forms, there are ways to encourage a certain kind of play, or at least ways to make it easier for referees to run them, and reward players who engage in them.

|

| The Cover Art of Forgotten Temple ... Feel the 80's Pastels |

PLAY IT LIKE A WARGAME

The most notable and clearly delineated of the Gygaxian Fortresses’ innovations or tools, and one generally applicable to other dungeon design forms, is the “Order of Battle”. An Order of Battle is a list of a faction or area’s hostile inhabitants including a variety of information: statistics, initial location, how long they take to respond to alarms, their tactics and how they will respond to various events.

While almost an essential part of any war game scenario, they are rare even now in RPG scenarios, though Gygax started experimenting with this design as early as 1978’s G1 - Steading of the Hill Giant Chief. The Order of Battle is extremely limited, specific to a single location, and fails to address issues like if and how long any surviving guards and pets in the Steading will take to respond to the Chief’s shouts or the sound of battle, but it is clearly an Order of Battle. It is designed to offer a referee an accessible format that will help run a tactical combat encounter and contains a list of a few of the essential elements of a more complex Order of Battle, specifically the area’s defenders’ immediate locations (though these could be better marked on the map as well), and a schedule of their HP. The key also includes one special tactic that the giant chief will use (his ballista/crossbow).

| STEADING - MOVING TOWARDS FUNCTIONALITY |

| AN ORDER OF BATTLE - FORGOTTEN TEMPLE |

While the second Order in Forgotten Temple is more extensive and informative, the first, for the “Valley of the Orcs” is notable in that it forms entire entry beyond notes about the orcs red and yellow heraldry, a map of their rather extensive caves (no key is offered), and a single line covering their treasure (a coin hoard in a chest) and noncombatants (including 120 defenseless orc babies). The encounter with the Jagged Knife Clan of Orcs appears as an almost entirely a tactical one, but in typical Gygax manner the orcs and have evicted a lamia from its cave and are now in a sort of guerilla war with the cat monster and its pack of leucrotta. Even these two fairly limited encounters dropped on Forgotten Temple’s overland map offer an opportunity for more then pure combat because suddenly there is the possibility of faction intrigue and for the characters to build relationships with either the lamia or the orcs, both of whom could be potential allies against the larger threat of the Mountain Giant and its Norker band (though I suspect both would want treasure for such risk, even with the party having killed off their rivals).

Beyond the useful tool of the Order of Battle, Gygax often provides a few other elements to better integrate infiltration and faction intrigue into his scenarios. These both purely map design elements that either make a tactical situation more interesting or allow the party clever ways to bypass strong points, but they also include various opportunities to assassinate or sabotage the foes within the fortress. B2 - Keep on the Borderlands has several such map elements, includes examples of the former, primarily secret doors that connect many of its factions’ individual cave lairs. The “forgotten room” between the two orc lairs offers a good example allowing a party that has invaded one of the orc lairs to access the leader of the other almost immediately after finding the secret door and potentially removing the second group’s leadership. Other secret doors allow access to the bugbear gang leader’s cave, provide access to the hobgoblin leader’s hidden rooms (including access from the far easier to infiltrate goblin lair), grant a hidden way into the temple of chaos and from the ogre’s lair to the goblin guardroom (and facilitate the goblin’s use of the ogre as a mercenary).

|

| THE MAP OF THE CAVES OF CHAOS - by Dyson Logos |

Similar map based tools to facilitate infiltration include roof or window access, such as the ability to descend into the courtyard of the steading in G1, and castle infiltration classics like secret postern gates or drainage channels that lead to a dungeon level. Even entire forgotten or abandoned sections of the dungeon (also found in G1) that can allow characters to create hideouts within the dungeon or lead to secret entrances. Beyond this kind of feature, Gygax’s maps are not usually very large or especially full of interconnections, but they, and the placement of specific areas within them do have an internal logic … they make sense, especially when one looks at them from a defensive or military perspective. There are guardrooms that watch entrances, areas where the humanoids that invariably defend Gygax’s dungeons can muster for a larger battle, living quarters and armories. This is also part of the Fortress design sensibility, the infiltrating players should be able to learn enough to guess where they are within the dungeon and what might be nearby. When one looks at the map of the hill giants’ steading in G1 it has four distinct areas: a central hall and yards, a cluster of buildings on the Eastern/left side where the giants live, and a barracks and armory in the North East. The Western or left side of the map is another jumble of buildings that contain servants, guest rooms, kitchens, and other functional spaces. Even the dungeon level of the steading is largely that, a dungeon where the Giants trap their orc slaves. The steading may be a fantastical space and even throws in some oddities in the dungeon level, but overall it makes sense. One won’t stumble from the kitchens directly into the chief’s chamber.

|

| THE STEADING MAP |

Gygax also expands on these map based opportunities with specific situations that provide opportunities to undermine his fortresses. In G1 we even have opportunities spelled out in the very sparse text: the party can steal the clothing of young giants and disguise themselves, negotiate with various dissatisfied maids, servants, and slaves for information, treasures or alliance, and the party can ambush individual giants such the numerous drunken guards or a “handsome giant warrior” who wants to show off in front of the giant maids in the servant’s quarters and will not call for help. Designing the Gygaxian Fortress is more than simply setting up a war game scenario, though this is part of it, it’s creating a space that offers opportunities and clearly defined for player actions and schemes and doing so with a variety of tools.

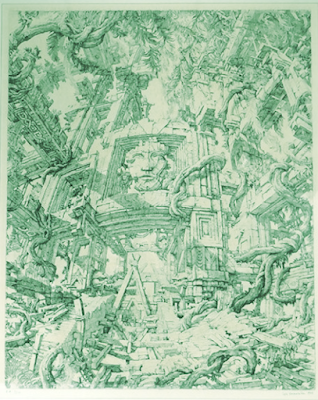

|

| ALTERNATIVE ART FOR FORGOTTEN TEMPLE JUNGLE TEMPLE - Erick Desmazières (1973) |

Gygaxian Naturalism

No discussion of Gygax’s design could be complete without reference to another of its key attributes, one that also adds to the functionality of his adventures -- “Gygaxian Naturalism”. The phrase was first widely discussed and defined, as with many OSR concepts, on James M’s blog Grognardia and means more or less a loose ecological or logical approach to RPG setting building. In the 2008 post, James M defines it as “[The] tendency, [...] to go beyond describing monsters purely as opponents/obstacles for the player characters by giving game mechanics that serve little purpose other than to ground those monsters in the campaign world.” James cites examples such as monster spells and abilities that have little or no effect on gameplay, and the long controversial inclusion of non-combatant humanoids in their lair creation process.

In an earlier post, Gygax’s naturalism also had an aesthetic aspect for James, found in the way the Monster Manual depiction of Orcus has elements of Medieval art and a less glossy or cliched appearance than the then new version on the cover of 4th edition’s Monster Manual. There’s an element of both functionality and aesthetics to Gygaxian Naturalism - it is both the grounding interconnectedness and understandability of Gygax’s worlds and his specific aesthetic. Gygax’s own aesthetic can perhaps be described as Osprey Publishing’s books on historical armies spiced with Tolkien and other mid-century fantasy and sci-fi authors.

This aesthetic is a good fit for Gygax’s adventures and does add to their playability because it allows a player to obtain a useful genre mastery of both the historical elements and much of the fantastical. Knowledge of medieval polearms provides a player with the option of using the hook on their bill guisarme to collect things from magical pools while reading Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions will give players knowledge of Gygax’s trolls and their weaknesses. The grounded element of Gygax’s aesthetic -- it’s “gritty” military or wargame armor and weapon variety helps place his adventures firmly in the “heroic” rather than “superheroic”. Again this reflects the way Gygaxian adventures match the tone of the 1960’s Commando film where the realism of the military aspects limit the super heroic aspects of the story and heroes. In Guns of Navarone’s climax the commandos have lost most of their explosives and must set a trap using the gun’s own ammunition - this sort of complexity can be compared with the less rigorous approach of more modern Action films (or even more video games), where large guns and vehicles are often destroyed by a single fragmentation grenade. The “realism” of the Commando film, while still stretched, dominates because weapons operate with predictable limitations, rather than as metaphors.

While Gygax’s aesthetic helps his adventures function, grounding players in concerns about equipment and imposing the same sort of stretched realism. This effect may fade as level increases and magic items and spells whose effects are far more metaphorical become common, but the grounding never entirely goes away. It's a great trick, and it isn't necessary to use either the same set of inspirational fantasy or inspirational history as Gygax to replicate the effect. References allow helpful because they grant players a way of grounding the world and give referees tools to better extrapolate detail and can be borrowed from whatever history one finds convenient (e.g. a warrior wearing a buff coat will likely have a lobster tail helmet will likely have a basket hilted saber for example), and as long as the references are accessible, they can serve as a source of detail and grounding for the game. References and accessible knowledge about the fantasy world are the real heart of Gygaxian Naturalism - what makes it function as a design tool because it's largely about forming an interconnection between elements of the adventure or setting and useful detail that players can discover and referee can extrapolate from. Borrowing from other, richer sources takes a lot of the load off of the adventure itself to provide detail.

Gygax himself never uses the term “Naturalism”, but comes close in his discussion of setting design in the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide and it has little to do with aesthetic or tone of Gygax’s adventures, instead he cautions that “Dungeons [and wilderness] must be balanced and justified, or else wildly improbable and caused by some supernatural entity which keeps the whole thing running - or at least has set it up to run until another stops it. In any event, do not allow either the demands of "realism" or impossible make believe to spoil your milieu. Climate and ecology are simply reminders to use a bit of care!” Following this, Gygax provides some examples of fantastical elements that could allow a setting with so many monstrous predators to make some kind of ecological sense and warns that players may demand to understand the world, but advise that the referee shouldn’t go too far attempting to simulate reality.

Gygaxian Naturalism isn’t just a way of visualizing a game world, in Gygax’s adventures it serves to ground the fantastic space by making it coherent and comprehensible. The hill giants' steading has kitchens, storage spaces, barracks, and other rooms one would expect in a fortified hall, with the other creatures encountered in the place are either servants (orcs, bugbears, and ogres), pets (dire wolves, a bear, manticores), vermin (troglodytes, giant lizards) or visitors (the cloud giant). Gygax goes further in The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth (1979):

“The pools support small, pale life—crayfish and fish, as well as crickets, beetles and other insects. Characters who listen closely will hear a number of small sounds, mostly those associated with the insects and other small life which inhabit the caverns. [... The caverns are also home to] bats, a few giant rats, many normal rats, huge nightcrawlers (3' to 6' long, no attacks), or various large-sized slugs and grubs. All are harmless. These are the usual prey for the larger creatures inhabiting the caverns.”

These two examples, I think of them as the giant’s cookpot and the huge nightcrawler, perform two distinct services to the referee and players, both of which are part of Gygaxian Naturalism. As mentioned above the cookpot sort of detail offers the party tools for unorthodox approaches to victory. The next meal for the majority of the giants is accessible. It is available to the party as a way to poison the majority of the giants (which of course many would successfully save against), but the giants' kitchen also represents a potential tactical advantage to a party that uses disguise to enter the main hall carrying something dangerous and pretending it’s the next feast course. A party might emulate the bugbears in the Caves of Chaos and offer skewers of meat, using the skewer as a weapon in a last minute sneak attack. A giant sized pot of stew (or hot oil pretending to be stew) is also a potential weapon. While few of these possibilities are described, though specific items such as potions of poison and delusion as well as dark elf wine that compels even the giants to drink to drunkenness are available, having kitchens and storerooms in the giants steading provides them as a matter of simple deduction and thought by the players. They are available because every person knows what might be in a kitchen and can imagine how one might use food and kitchen supplies to cause mayhem.

The "nightcrawler" example is less immediately accessible in game, but it is still potent. By offering a fantastical ecology for the Lost Caverns Gygax has given the referee tools for description and explanation -- a sense of what happens in the depths when the characters aren’t there with monsters hunting worms and nibbling at strange mushrooms in the dripping darkness. As simple as these ideas are, they make it easier to describe spaces and the activities of the dungeon’s inhabitants. They offer clues to answer the sorts of questions players routinely ask: “What’s in the ogre’s pocket” or “what are the goblins doing”? While not immediately gameable they encourage gameability because they provide continuity and give accessible details to the fantastic space.

Keying For Conflict

Beyond the general design techniques and specific tools or scenarios, Gygax’s keying is also focused on building a fortress for siege and infiltration. Fundamentally this means focusing on enemy/monster organization, behavior, and tactics in his keys, while adding just enough environmental detail to sketch a space. Gygax’s keys, are sparse where they describe spaces, but grounded in exact physical description: dimensions, basic materials, and especially notable features. These are usually sufficient, as Gygax also had a knack for providing a line or even a few evocative adjectives that give a referee enough to work with in the context of the adventure.

This description of “the Mound of the Lizardmen” in Keep on the Borderlands is a good example of Gygax’s typical approach:

“The streams and pools of the fens are the home of a tribe of exceptionally evil lizard men. Being nocturnal, this group is unknown to the residents of the KEEP, and they will not bother individuals moving about in daylight unless they set foot on the mound, under which the muddy burrows and dens of the tribe are found. One by one, males will come out of the marked opening and attack the party. There are 6 males total (AC 5, HD 2 + 1, hp 12, 10, 9, 8, 7, 5, #AT 1, D 2-7, MV (20’) Save F 2, ML 12) who will attack. If all these males are killed, the remainder of the tribe will hide in the lair. Each has only crude weapons: the largest has a necklace worth 1,100 gold pieces.

In the lair is another male (AC 5, HD 2 + 1, hp 11, #AT 1, D 2-7, Save F 2, ML 12) 3 females (who are equal to males, but attack as I + 1 hit dice monsters, and have 8, 6 and 6 hit points respectively), 8 young (with 1 hit point each and do not attack), and 6 eggs. Hidden under the nest with the eggs are 112 copper pieces, 186 silver pieces, a gold ingot worth 90 gold pieces, a healing potion and a poison potion. The first person crawling into the lair will always lose the initiative to the remaining lizardman and the largest female, unless the person thrusts a torch well ahead of his or her body.”

This is a longer example of Gygax’s early and best known style of keying, though it describes an entire lair/location with reference to a simple map. It should be obvious that the primary focus here is on the combat or tactical potential of an encounter with the lizardmen. Reading a single paragraph we get the lizardman band’s: makeup (7 males, 3 weaker females, and 8 children), behavior (“evil”, nocturnal, predatory, and territorial about their mound), battle tactics (individual emergence and attack of the warriors, the dangerous tunnel ambush of the mound dwelling male and females), and a potential counter to this dangerous tactic (caution and fire).

| LIZARDMAP! |

“a mound of black raw earth rising from the marsh, denuded of the lilies and reeds that fill the surrounding pools, and pocked with narrow dark holes, leading inward to narrow tunnels, half flooded and stinking of rotten swamp plants, urea, and dead fish.”

This kind of basic description is easy to reach for with this sort of space, and works in the context of Keep on the Borderlands earthy vernacular fantasy, it’s also somewhat limited. Neither the Lizardmen themselves or their treasures are meaningfully described. The only description of these creatures is of their “exceptionally evil” nature, a difference from the standard “neutral” lizard man (who still enjoys “feasting” on people) as described in Moldvay Basic (which was likely written after B2). However Basic Dungeons & Dragons description of Lizardmen as “water-dwelling creatures [who] look like men with lizard heads and tails” is likely to have been informed by Gygax’s conception of them here -- it’s excluded from both Greyhawk and the AD&D Monster Manual where no physical description is offered, though the desire to eat people is noted in both places and image in the Monster Manual is more than sufficient.

Again, across Gygax’s writings, he emphasizes the behavior, demographics and mechanical statistics of the foes. With the lizard men this works well enough -- the name alone describes them rather well and it’s easy for a referee who needs more description to pull from their own common knowledge of lizards. When I first played B2 in 1983, the twelve year old running the game was familiar with anoles and so our lizardmen were green and brown, with tiny scales, long narrow heads, and throat sacks. Presumably at another table they were iguana based or jagged toothed dinosaur people. By focusing instead on the tactics, culture (as much as feasting on people or sometimes living in huts is culture), Gygax centers his game design around combat and negotiation with his monsters, especially his “humanoid” monsters, who generally receive longer write ups. In Gygax’s less compelling work this tendency towards a sort of shallow military sociology expands, perhaps excessively, and sometimes in ways that create a sort of absurd taxonomy or racial essentialism that has been the subject of much critique. In the context of Gygax’s best works however, especially in adventures where he is presenting singular encounters without extraneous social commentary, it is good design and hard to find objectionable.

The focus in these adventures is on the most likely encounter the players will have with the “monsters”. Often, such as at the Lizard Mound, this is combat -- a violent altercation, proceeding first through near ritual combat, and then a horrific ambush in the muddy tunnels below - likely a fatal encounter for a low level party. Yet Gygax has given us enough about lizardmen and their lair here in a short paragraph, and in the supporting text of Moldvay Basic (or AD&D if one was playing an early edition of B2) to give referees some support for other possibilities. The lizardmen want to eat people but also value treasure, speak their own language, prefer to hunt at night and by ambush, and have some sense of ritual and honor (hence the challenge style attack on trespassers). There are possibilities for negotiation, and of course betrayal - being stalked by murderous nocturnal lizardmen with a penchant for eating people. It’s enough that even this simple, one paragraph wilderness encounter, nearly free of description, could be used as the bedrock of a regional faction should unlikely events occur in one’s game.

Where Gygax’s style suffers is when it expands too far, such as the pages’ long description of the Drow in Vault of the Drow. The dry and tactical about equipment and troop types would be better included in adventures and related to specific encounters with drow, and it becomes messily intermixed with details about the drow’s matriarchy and simplistic fairy-tale like history of drow society. Similar breakdowns occur when Gygax must describe stranger spaces, such as the subterranean fairyland the drow inhabit. While there are some sound descriptions of places like the Drow capital, Gygax attempts to maintain the style of his tactical and referential descriptions, but expands them and mixes in complex prose, often resulting in a key that’s still functional, but loses the accessibility found in his best work.