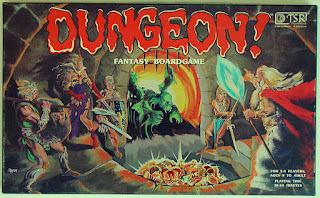

THE BOARD GAME - DUNGEON! Mid 80's box cover of DUNGEON!

In the early and mid 1970’s David R. Megarry, a member of the same gaming group as Dave Arneson and David Wesley (of Braunstein fame) and player in Arneson’s 1972 Blackmoor campaign, began to play around with the concepts he learned dungeon crawling in Blackmoor to create his own game: “Dungeons of Pasha Cada”. He sent initial handmade copies were to friends and attempted to publish through Parker Brothers but was rejected. Eventually, as part of the absorption of the Minneapolis-St. Paul gaming group, Megarry joined TSR and his game was published as DUNGEON!, with Gygax, Steve Winter, and others were added to the game's authors' list.

Built from memories of Blackmoor and the Chainmail Fantasy Supplement for monsters, spells, and concept, DUNGEON!’s rules are a brew of mid-century war games rules that may ultimately lead back to the dawn of American war gaming - Charles A. L. Totten’s Strategos (1880). While DUNGEON! is first and most importantly a board game, in the context of playing old fantasy RPGs, DUNGEON! represents an alternate evolution of Blackmoor, Greyhawk and Dungeons & Dragons.

DUNGEON! was published by TSR, only tangentially part of the Dungeons & Dragons by implication, where it remains (Wizard’s of the Coast last published a version in 2014) somewhat unchanged from the early editions. DUNGEON!'s monster and adventurer selection is firmly set in the implied setting of early Dungeons & Dragons and its name and aesthetics are so similar to early Dungeons & Dragons that in the 1980’s it was often presented as or assumed to be (at least by the folks I knew) some sort of introduction to the game for the uninitiated (its rules with their add for Dragon Magazine imply this as well). DUNGEON! though is a very, very different game from Dungeons & Dragons, both in its mechanics and goals. DUNGEON! has interesting design, intentional design even, with effort put into making a fast, competitive board game that includes RPG elements such as character asymmetry and advancement.

DUNGEON! IS INTENTIONAL DESIGN

Dungeon isn’t a roleplaying game, it’s not a version of Dungeons & Dragons, or even Blackmoor - notably it doesn’t have a referee or dungeon master, it offers no open ended obstacles based on description or faction intrigue. DUNGEON! doesn’t even resemble contemporary refereeless games as it has no elements of shared narrative control or storytelling. It is just a board game, where control of setting and “story” are lodged firmly with the designer and the random determinations of the dice - the players of course have some agency in that they decide where their adventurers go and what routes they take, but it doesn’t offer control in the way that contemporary referee free RPGs like Fiasco do. While DUNGEON! isn’t a roleplaying game in the normal sense, it still contains some of the basics of dungeon exploration: navigation as a puzzle, risk and reward calculations and turnkeeping.

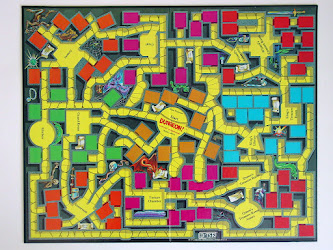

|

| The Original Board for DUNGEON! |

Combat consists of rolling 2d6 aiming for a target number based on adventurer class and the monster. A second roll determines the result of a lost combat, with only a 2 resulting in the “death” of the adventurer, and 3 or 12 resulting in a serious injury, loss of all treasure, and retreat back to the stairs. That’s around an 11% chance of serious loss (most negative results end in retreat, loss of a turn or single treasure) assuming a failed first roll. Once a monster is defeated the adventurer collects the treasure or possibly a magic item that will improve their future chances by looking at cards in other rooms (crystal balls, esp medallions) or adding to their attack roll (magic swords). Wizards alone can cast spells, mostly to attack monsters without risk of reprisal. Advanced rules exist allowing players to ambush each other.

|

| Low Level Monsters and Treasure |

These simple rules are meant to create a high risk competitive board game, they don't support character development or cooperation, and they don't present open ended problems beyond player strategy in navigating the board and judging risk. Looking at them closely, or playing DUNGEON!, it's clear how well the rules manage to deliver on this simple concept and how complex player decisions can become.

Beyond this simple, perhaps even “ultralight” game, DUNGEON! creates variation and complexity by breaking up the map by difficulty (the colored levels) and encouraging more powerful adventurers towards the more difficult regions with their larger treasures and tougher enemies. Of course weaker adventurers (elves and heroes) can also try to defeat these more dangerous enemies for the chance to rapidly meet their treasure goals, or wizards and superheroes can try to slowly accumulate wealth in the less dangerous regions. The combat system, while perhaps bizarre at first glance, works for precisely the single game, competitive nature of DUNGEON! The combat rules even add more complex decision making without additional rules or in game steps. DUNGEON! encourages risk taking, because of the linkage between treasure value and monster difficulty as well as risk v. reward judgments, as if you lose a combat and drop a treasure the monster gets it, encouraging a rematch or race to the pile of treasure if the loss forces a full retreat. Nor is this simply the replacement of hit points with treasure, combat remains fast, two rolls per turn, and high risk regardless of adventurer type. Likewise the penalty for failure (which is quite random after all) is never so onerous as to force the player out of the game (with the optional rules for returning after death). These rules might not work in a cooperative, multi-session role-playing campaign, but they are great for a simple board game.

This is the extent of DUNGEON!’s risk and reward calculation, but it manages to incentivize the sort of play it’s designed for (exploring the dungeon and making calculations about risk in a race for treasure) while providing penalties and bonuses that work together with the basic structure of the race for wealth, and significant variation between players based on their adventurer. Megarry's intent to create a competitive board game that offer players a sense of exploration and the trappings of fantasy dungeon adventure succeeds with a simple ruleset, and it largely does so because it drills down to a core goal, the recovery of treasures, and a few key complications: combat with monsters and choices on how to best navigate a fantastic space. He willingly dispenses with or simplifies many inherited mechanics (such as measurement based movement) in service of these goals and complications.

|

| DUNGEON! 1975 Box Cover |

DUNGEON! does what it seeks to do, provide a competitive dungeon exploration game that has the trapping of fantasy adventure and some of the basic elements of the classic fantasy dungeon crawl - navigational choices, risk taking and risk v. reward calculation. It even has the chance of using shortcuts (its secret doors), to better move about the map. What DUNGEON! lacks is the sort of obstacle based creative play that defines roleplaying, but there’s nothing to suggest its highly simplified rule set doesn’t provide a base to create rules for more traditional roleplaying within the context of a competitive board game. Indeed, in its early years house rules (mostly additional classes, spells, items etc) were offered in Strategic Review and Dragon magazine. The primary limitation for DUNGEON! is that it remains a board game which keeps it from becoming a simple roleplaying game because without a referee it can’t offer complex tactical, obstacle, or puzzle situations that require adjudication.

However, looking at the earliest era of fantasy roleplaying, it's easy to wonder how much like a board game (or perhaps war game) early play was. It is difficult to find believable or informative accounts from early Blackmoor or Greyhawk (Dave Arneson’s and Gary Gygax’s proto-Dungeons & Dragons campaigns) because so much of the early history was muddied during the pair’s various lawsuits. For an absurd example, Gygax allegedly claimed that Tolkien had little influence on Dungeons & Dragons when sued by the writer's estate. Similar obfuscation, faulty memory, and conflicting claims surround accounts of the early campaigns. Still, it’s pretty clear that some variation of the Chainmail rules were used in Blackmoor’s combat (making it one or two rolls and extremely deadly). Another clear similarity to DUNGEON! found in Dave Arneson’s First Fantasy Campaign and from Underworld & Wilderness Adventures (the third book of the original Dungeons & Dragons box set) is the idea that the dungeon is randomly generated before play by the referee. Rooms are stocked according to formulas and tables and treasures and monsters randomized by level. Partially by preference, partially because of the sparse details of Chainmail and early Dungeons & Dragons, early published adventures, especially 1976’s Palace of the Vampire Queen, share this sort of ultra-minimal design and look very much like a pre-prepared map for DUNGEON!

|

| The Board got Better |

All of this suggests to me something other people have pointed out about early Dungeons & Dragons - that it takes influences from and shares a lot of elements with mazes and “maze games” which were evolving at the same time as Dungeons & Dragons aided by the introduction of computers. Mazes, found in books of varying quality and design, including the best sellers of Vladimir Koziakin, were part of a 1970’s childhood - a fad in the same society and same moment as the birth of Dungeons & Dragons, and would be sidelined to a greater or lesser degree by computer games. Mazes of course predate Dungeons and Dragons and the 1970’s by hundreds, even thousands of years, with the concept found most relatably for D&D in the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur.

|

| KoD:M Core Set - DUNGEON! Evolution |

|

| Some 16th Century Italian Mazes Woodcuts from Francesco Segala’s Libro de laberinti |

LEARNING FROM DUNGEON!

DUNGEON!'s exploration rules are where it both most resembles and most interestingly diverges from early Dungeons & Dragons. Much of this similarity is the core experience of plotted movement and turnkeeping, but the arbitrary nature of traps (in early D&D they trigger on a 1 or 2 without detection opportunity and the only defense to deadly ones is a Saving Throw), identical secret door detection roll (the method is different as without a referee DUNGEON! must mark them for the players), and the random generation of monsters and treasure, suggest a board game-like feel to both underworld adventures using the 1974 ruleset without adaptations. Combat might be similarly fast and deadly (or “fast and furious” as noted in Underworld and Wilderness Adventures), if Chainmail’s combat system is used, though unlike DUNGEON!, combat in Dungeons & Dragons lacks the carefully structured partial loss mechanic that uses treasure loss and retreat to make combat tie in so well with the games’ goals.

The greatest similarity between DUNGEON! And early D&D is the one noted above - the core aesthetic of fantasy adventurers exploring an underworld maze and the influences that create it. These influences take DUNGEON! to a fundamentally different design space from Dungeons & Dragons, but because of a shared basis and aesthetic, some of its ideas remain useful for looking at D&D’s subsystems and traditions.

Abstracted Movement: The exploration rules of DUNGEON! notably diverge from Dungeons & Dragons because they are “tile” or “room” based -- abstracted. There’s nothing mysterious to this, the heritage of Blackmoor and Dungeons & Dragons was tabletop wargames, where ranges, movement, and charge distances were of great importance and measured with ruler in inches or millimeters. Early Dungeons & Dragons also adopts the inch as an official unit of measurement - an inch represents 10’ feet indoors and triple that outdoors. DUNGEON! though is a board game, where the tradition is movement by spaces. The spaces in DUNGEON! Are the corridors, each broken into several spaces, and each room. Adventurers move at a flat rate of 5 spaces per turn, and the distances between the rooms (each of which contains treasure and a monster) is carefully calculated with a balance between movement and room encounters in mind.

DUNGEON!’s movement may not be as exact as Dungeons & Dragons, but it’s entirely reasonable as a simple way to model movement. Generally D&D parties move at the rate of their slowest member, and the main reason to track movement is because it corresponds to the passage of a Turn: the depletion of light, increased exhaustion, and a risk of a random encounter. A Turn is usually defined as 10 minutes, but for the game the real unit of time and distance is the time between random encounter rolls and the distance of roughly 120’ (In the earliest edition the players can move twice each turn, and in later editions random encounters are generally checked every two Turns). Looking at most dungeon maps one finds that (perhaps thanks to graph paper size), this is quite a long stretch of corridor to travel between risks. It may be a simplification to reduce party movement to one corridor or room per Turn and random encounter or exploration/hazard die roll (perhaps increased to two moves when moving quickly/running, or reduced to 1 move per two turns/rolls if encumbered). Simplification or not, abstracted movement won’t really change much during exploration, and it offers the benefit of dramatically reducing the number of calculations the referee needs to make about distances travelled or described and time spent. Obviously longer corridors or gigantic rooms can be noted as taking two Turns (and rolls) to traverse.

As mentioned here before, if abstracted movement leads to seeming contradictions about time or arguments that the characters should be able to move faster, consider the arguments for abstracted time as well. A Turn need not be exactly ten minutes ... How do the characters know how much time passes in the stressful environment of a dungeon? Plus, the dungeon is a magical and antagonistic place, who’s to say time passes at a normal rate there? Perhaps it’s best to consider the Turn a significant length of time, however long it takes to move down a corridor, or get one’s bearings in a room, rather than any specific period of minutes and seconds.

|

| Dyson Logos maps the DUNGEON! Board |

There are other less general lessons found on DUNGEON!’s board. DUNGEON! utilizes nodal design. Nodal dungeon design is a concept popularized in 2012 by KLDavies of the In My Campaign Blog. Nodal design is a means of both simplifying large dungeons and breaking down a megadungeon project into manageable parts, but it’s also a way of conceiving large fantastical space by breaking it up into themed regions rather than individual rooms and focusing design on their interrelation.

DUNGEON!’s nodes are incredibly simple, with the most minimal of theming found in the names of the large chambers and the difficulty of the monsters found within, but DUNGEON! is a simple game. DUNGEON!’s “level” still functions to direct play by splitting the adventurers up based on risk tolerance and adventurer power level - just as nodes in a more complex megadungeon can. The colors of the board “levels” are a lesson of nodal design as well -- they clearly signpost risk without depending on verticality (though they don’t completely predict it - monster cards vary considerably), because without information players can’t make useful or informed decisions. In a proper RPG dungeon theme and dungeon dressing will take the place of the simple colored rooms on the DUNGEON! board, but the principle remains -- give players information about risk and clearly signpost relative changes in danger level of a region.

Nodal design is primarily useful as an approach to adventure design, and it can become fairly complex, but because of DUNGEON!’s simplicity it illustrates ways to do this fairly effectively: build out a large dungeon by theme and risk level, signpost that risk level (via rumors or simply theme) and provide limited paths (both secret shortcuts and obvious but less safe or longer ways) between nodes.

Treasure Loss as a Price for Survival: DUNGEON! Doesn’t have hit points, it barely has any resources at all - limiting them to wizard spells, magic items discovered in game and treasure recovered, but it utilizes them well to create a structure of penalty for failure that’s effective but not punitive. It’s always worth remembering when designing adventures that characters in Classic games are generally exploring the mythic underworld to recover treasure. Yes, there’s always the risk of character death, but HP loss isn’t the only setback they can face. While a set of house rules (especially for players less comfortable with character death such as children or those coming from other play styles) could easily be created based on DUNGEON!’s treasure loss rules (defeat leads to loss of treasure or equipment and return to town without experience gain) this isn’t the main point these rules make. Even in a more traditional game, treasure, equipment and supplies all represent things of value to players and characters. Their loss or depletion effect the overall success of an adventure, likely increase risk for further exploration, or can add to the reward of an obstacle (as when a DUNGEON! monster succeeds in stealing a treasure from an adventurer).

Wandering Monster Acceleration: DUNGEON! has alternate rules, one for PVP ambushes that makes sense in the context of the board game, but doesn’t offer much to cooperative RPG play, and another adding wandering monsters. At the start of each turn after a monster has been defeated, a table and die roll place a monster it in the corridors of a random “level” (no monster is placed if none exist for the appropriate level) where it will attack the strongest adventurer wandering those halls. This rules makes wandering monsters in DUNGEON! Function somewhat differently than in Dungeons & Dragons and with a somewhat different purpose. Random encounters are usually a counterweight to player caution, a risk that arises for each turn spent in the dungeon, offering little or no reward and complicating exploration. They encourage players to move quickly, take risks, try to push through obstacles and reward finding secret or alternate paths. In DUNGEON! However they are a clock that increases difficulty and risk the more monsters have been removed from play. The wandering monster system also rarely restocks rooms (they will retreat to a room if they succeed in stealing a treasure from an adventurer) but it’s primarily a mechanic to accelerate risk in the end game of DUNGEON!. In specific RPG scenarios a similar system could work - especially in siege scenarios where each set piece encounter increases the risk of detention and patrols from the location’s inhabitants. I suspect this would work better in an RPG if combat worked as a trigger to replace less dangerous random encounters (vermin and noncombatant) with more dangerous patrols. As with DUNGEON!’s treasure loss mechanics, the lesson here is less of something to borrow exactly and more of a gateway to alternate ways of thinking about a common mechanic.

Adventure board games can present an interesting reflection on RPGs, especially for the location based exploration play style, and I’d argue that this is because, like DUNGEON! They are largely built from the same influences: the maze and war game, a hybrid form that’s better than the sum of its parts. DUNGEON! also acts to remind us that sometimes simple rules work well and that intentional design, where mechanics are built to deliver a specific type of play can work to create tightly defined smooth running play experiences. I’d contrast this style of design with accretive design, where rules, subsystems, and complexity multiplies through play, and suggest that if one is having trouble with complexity to look towards one’s design goals and play style. A reexamination of basic rules, especially from a different perspective, can lead to useful simplification and streamlining.

Very enjoyable read, and great presentation.

ReplyDeleteMeritorious.

Treasure loss as the price of survival is an idea that really resonates, I think. Sonic the Hedgehog being another prime example of its use.

ReplyDeleteSonic was after my time with consoles, but yes I understand he sprays gold when he's struck. As a D&D mechanic I think it most directly translates to the rule in OD&D that intelligent foes can be distracted from chasing the party with gold. Not sure how I'd use it more directly without a setting overhaul?

DeleteBeing a Nintendo kid, I am likewise pretty ignorant of the intricacies of Sonic lore. Still, an interesting correlation. The idea floats through the zeitgeist.

DeleteJust realized this is also the loss/death mechanic in Dark Souls! Shocking coincidence that a Dark Souls RPG has just been announced!

Deletebut ...

It will be 5E based, so non-magic item treasure has no meaning. The irony! It's like O. Henry is writing the story of the RPG industry.

I picked up Dungeon! circa age 8 believing it was the Dungeons & Dragons game (after discovering my error, I would get the Moldvay set some time less than a year later). I credit it with giving me a basic understanding of MUCH of the peculiarities of D&D's brand of fantasy as well as its assumptions of play. Considering the few illustrations of monsters in the Moldvay book, it was useful to have the illustrated monster cards.

ReplyDeleteI've spent a lot of time with Dungeon! over the years. Still have my original (40+ year old) set on my shelf...my kids have played it quite a bit. I've purchased later edition copies, designed (and printed) my own cards for the game, written house rules for the thing, analyzed its game play. At one point, I tried to rework the board into a D&D dungeon (the six levels being commensurate with Gygax's suggested dungeon size) but found some issue with the scale that stopped the exercise.

I adapted the Chainmail-based 2d6 combat roll in Dungeon! for my Chainmail based version of OD&D, Five Ancient Kingdoms (Chainmail has very few fantasy monsters compared to Dungeon! but the rolls to defeat are more-or-less the same for heroes vs. superheroes vs. wizards, etc.).

The idea of treasure/equipment loss as an alternative form of failure is pretty cool, though I can see it getting a little "story gamey" if the ability to exercise such an option is left in the hands of the player...and even if (heavens!) left as a matter of DM fiat. I've done similar things with other (personal) game designs (not D&D) and found the results unsatisfying. But it IS interesting, and probably a concept worth exploring further.

The Dungeon! rules I have are a later edition (1979 or 1980, I think) and include neither the "ambush" nor "wandering monster" rules, so I can't comment on how they work or how they might be adapted. However, I'm interested in BOTH these facets of D&D play, so I wish I *did* have a copy of them.

For me, Megarry is right up there with Gygax and Arneson.

Your childhood DUNGEON! experience share a bit with mine. My friend had it and I was convinced it was D&D before I really knew anything about D&D, and we played it a few times. As you say the box, board, and card art were inspiring and I suspect it brought fair number of people into the hobby (along with the wire cored rubber carrion crawler toy, the influence of which has yet to be fully appreciated!) I never had my own copy, but I'm sure that if I did I would have hacked the heck out of it the same as you did, especially as it has pretty robust solo rules.

DeleteFor equipment loss, I agree it doesn't generally make much sense in a campaign based cooperative game like D&D, but it serves as a useful reminder that players don't just value their PC, they value their PC's stuff almost as highly. Threats to equipment are something I don't see as much these days, but they are very much part of the early games - that there are multiple armor and weapons destroying monsters even in the LBBs small selection of foes is telling.

Megarry's DUNGEON! is an impressive work, and as I mentioned in the post it's really a neat insight into how early Blackmoor dungeons likely worked. In general digging into the early RPG and related rules, as well as the games and pastimes that seem to influence them (Maze books ... someone should really dig into that connection more) with a focus on how to elevate exploration to the same level of importance as combat has been interesting. The "board game" aspects of early D&D may have been ignored or pushed aside as the hobby has evolved, but they offer some eye opening ideas that feel pretty applicable still.

I found a copy of the rules online and read through those and they had the PVP/ambush and random monster/restocking rules. They had the same sort of typewritten charm as the LBBs like something from the 1970's, so I figured they were the original box, but who knows. They might even have been house rules, though I somewhat doubt it.

Forget "inspiring"...I would not know have known what a green slime, black pudding, or purple worm was supposed to be without Dungeon! acting as a knowledge base for my young brain (no such illos included in MY B/X books...).

DeleteRegarding "equipment destruction:"

Reading 5E, it's interesting just how passe the idea of having "stuff" has become, such that characters are limited in the amount of magical items they can equip and the general usefulness of equipment. Almost as if the evolution of the game has been A) players don't like losing their stuff, B) monsters and such that destroy stuff get downplayed and removed, C) players end up with too much stuff, D) stuff gets removed from the game.

I have a LOT of 5E thoughts to write about right now.

Looking forward to reading those thoughts!

Delete