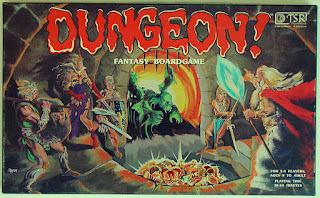

THE BOARD GAME - DUNGEON! Mid 80's box cover of DUNGEON!

In the early and mid 1970’s David R. Megarry, a member of the same gaming group as Dave Arneson and David Wesley (of Braunstein fame) and player in Arneson’s 1972 Blackmoor campaign, began to play around with the concepts he learned dungeon crawling in Blackmoor to create his own game: “Dungeons of Pasha Cada”. He sent initial handmade copies were to friends and attempted to publish through Parker Brothers but was rejected. Eventually, as part of the absorption of the Minneapolis-St. Paul gaming group, Megarry joined TSR and his game was published as DUNGEON!, with Gygax, Steve Winter, and others were added to the game's authors' list.

Built from memories of Blackmoor and the Chainmail Fantasy Supplement for monsters, spells, and concept, DUNGEON!’s rules are a brew of mid-century war games rules that may ultimately lead back to the dawn of American war gaming - Charles A. L. Totten’s Strategos (1880). While DUNGEON! is first and most importantly a board game, in the context of playing old fantasy RPGs, DUNGEON! represents an alternate evolution of Blackmoor, Greyhawk and Dungeons & Dragons.

DUNGEON! was published by TSR, only tangentially part of the Dungeons & Dragons by implication, where it remains (Wizard’s of the Coast last published a version in 2014) somewhat unchanged from the early editions. DUNGEON!'s monster and adventurer selection is firmly set in the implied setting of early Dungeons & Dragons and its name and aesthetics are so similar to early Dungeons & Dragons that in the 1980’s it was often presented as or assumed to be (at least by the folks I knew) some sort of introduction to the game for the uninitiated (its rules with their add for Dragon Magazine imply this as well). DUNGEON! though is a very, very different game from Dungeons & Dragons, both in its mechanics and goals. DUNGEON! has interesting design, intentional design even, with effort put into making a fast, competitive board game that includes RPG elements such as character asymmetry and advancement.

DUNGEON! IS INTENTIONAL DESIGN

Dungeon isn’t a roleplaying game, it’s not a version of Dungeons & Dragons, or even Blackmoor - notably it doesn’t have a referee or dungeon master, it offers no open ended obstacles based on description or faction intrigue. DUNGEON! doesn’t even resemble contemporary refereeless games as it has no elements of shared narrative control or storytelling. It is just a board game, where control of setting and “story” are lodged firmly with the designer and the random determinations of the dice - the players of course have some agency in that they decide where their adventurers go and what routes they take, but it doesn’t offer control in the way that contemporary referee free RPGs like Fiasco do. While DUNGEON! isn’t a roleplaying game in the normal sense, it still contains some of the basics of dungeon exploration: navigation as a puzzle, risk and reward calculations and turnkeeping.

|

| The Original Board for DUNGEON! |

Combat consists of rolling 2d6 aiming for a target number based on adventurer class and the monster. A second roll determines the result of a lost combat, with only a 2 resulting in the “death” of the adventurer, and 3 or 12 resulting in a serious injury, loss of all treasure, and retreat back to the stairs. That’s around an 11% chance of serious loss (most negative results end in retreat, loss of a turn or single treasure) assuming a failed first roll. Once a monster is defeated the adventurer collects the treasure or possibly a magic item that will improve their future chances by looking at cards in other rooms (crystal balls, esp medallions) or adding to their attack roll (magic swords). Wizards alone can cast spells, mostly to attack monsters without risk of reprisal. Advanced rules exist allowing players to ambush each other.

|

| Low Level Monsters and Treasure |

These simple rules are meant to create a high risk competitive board game, they don't support character development or cooperation, and they don't present open ended problems beyond player strategy in navigating the board and judging risk. Looking at them closely, or playing DUNGEON!, it's clear how well the rules manage to deliver on this simple concept and how complex player decisions can become.