|

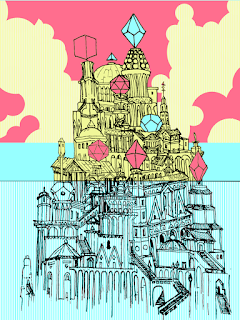

| Trampier from the 1st Edition Monster Manual |

These days it feels like the Post OSR spends a lot of time reinventing things that people wrote on blogs in 2010, or stumbling into the same well known solutions and declaring they have "fixed" the play style. Part of this is a lack of information for people new to these kind of games, exacerbated by the lack of citations among the hundreds of retro-clones that claim to be OSR games. There's little help for this, and as much as introductions to OSR theory like Philotomy’s Musings, Matt Finch’s Quick Primer for Old School Gaming, or Milton, Lumpkin and Perry’s Principia Apocrypha are useful documents and helpful introductions, the majority of OSR wisdom exists as scattered blog posts and in the minds of people who have engaged with the play style over the past 20 or so years. People don't read blogs anymore, but even if they did ... these bloggers, designers, referees, and players have a tendency to fall back on maxims when asked to explain elements of the play style, and it’s not the most efficient way of communicating craft and knowledge.

Worse, as the actual creation of the maxims recedes into the past, clouded by memory's failings and wearing into the grooves of dogmatic repetition, they have begun to take on the force of natural laws rather than suggestions or explanations of design decisions and play culture. The power of nostalgia and orthodoxy transforms simplifications and shorthand for larger, complex concepts into definitions that are frequently misinterpreted or carried to lengths that subvert their original meaning and damage the very type of play they were meant to support.

YOU CAN NEVER GO HOME AGAIN

Maxims have such a power in the OSR because it was forced to deal with the convoluted history of early Dungeons & Dragons. It’s often, and falsely, claimed that the goal of the OSR was to play games in the manner of some ideal past table: Gygax’s basement in Lake Geneva, or “the way D&D was meant to be played”. While some undoubtedly tried, this claim and any efforts towards it that actually happened is mostly nostalgic invention, a blend of cognitive distortions and bias that includes: rosy retrospection, survivor’s bias, selective abstraction, the masked-man fallacy and the halo effect. The problem being, that even where it’s discernible through faulty memories, self aggrandizing claims, and lies made up during IP litigation, the play style of early RPGs was constantly in flux. Dungeons & Dragons showed a great deal of conflict and transformation within play style from the first, and even within the 1974 edition. For example, the "Alternate Combat System" alone suggests an entirely different play style then the combat rules for Chainmail that were originally intended for the game. Worse, depending on one’s prior experience or influences a variety of play styles and design approaches all seem to fit within the description of “Old School” RPGs. The bloggers, referees, forum wits, and designers of the OSR struggled to articulate exactly what they wanted, which wasn’t uniform among them in the first place.

Instead of representing a “rediscovery” of a fully functional set of rules, procedures, design ethos, and play culture of Gygax's golden age -- somehow lost or destroyed by some ever growing cast of villains (the Hickmans, the Blumes, Lorraine Williams, Patricia Pulling and the Satanic Panic, Dungeons & Beavers, Hasbro, Vampire Larpers, Organized Play, or ... as always ... Young People), the OSR was always a place of invention, adaption, and revaluation. The OSR play style, to the degree any exists, was a new thing that evolved over time in the 2000's and 2010's, influenced by and partially formed from original early RPG texts and long-term play experiences of its members -- but necessarily taking in the various ideas and work in RPGs from 1974 to the present. Pithy maxims acted to anchor this decades-long aggregation of hundreds of peoples’ ideas and experiences into vague statements of general principle. "Rulings not Rules" is a phrase that one shares like a secret handshake, even if it's meaning isn't especially clear. Such statements are great for forming group identity (far more pleasant and long lasting than railing against a cast of villains and blaming them for a rupture from the nostalgic ideal) … but they don’t actually explain how to play the game.

7 MAXIMS to DeCODE

Maxims differ from aphorisms in that they present themselves as little truths, almost with the force of natural laws. Aphorisms instead ask their audience to think about them, and often hint at paradoxes or complexities in a way maxims don’t - and again this is where maxims are great tools for forming group identity, but less effective at teaching or giving their audience any sort of deep understanding.

The following maxims were common in OSR spaces and continue to be cited in much of the discussion around OSR and Post-OSR play style. I haven't generally listed their originators, though I suspect that most of them can be traced to a specific blog post or forum thread, largely because I am lazy, and they are always presented outside of their original context. Without it, they have changed meaning with time, and each is an effort to condense and simplify complex concepts or even arguments from or between numerous other contributors. Instead, all I can offer is my criticisms of the maxim (based on observations of how I've seen it used) and then my personal understanding as someone who was there, or at least peering though keyholes and standing in the shadows, when most of these maxims were hashed out. Generally this is a positive reading.